Over the years, people have added or adjusted the chart to fit their needs, creating different types of quality control charts that look and operate in slightly new ways. Like many visualization types, there are multiple variations and types of control charts available to users. If quality control is vital to your business - and it probably is - you need to utilize control charts to determine when problems exist that require your intervention.

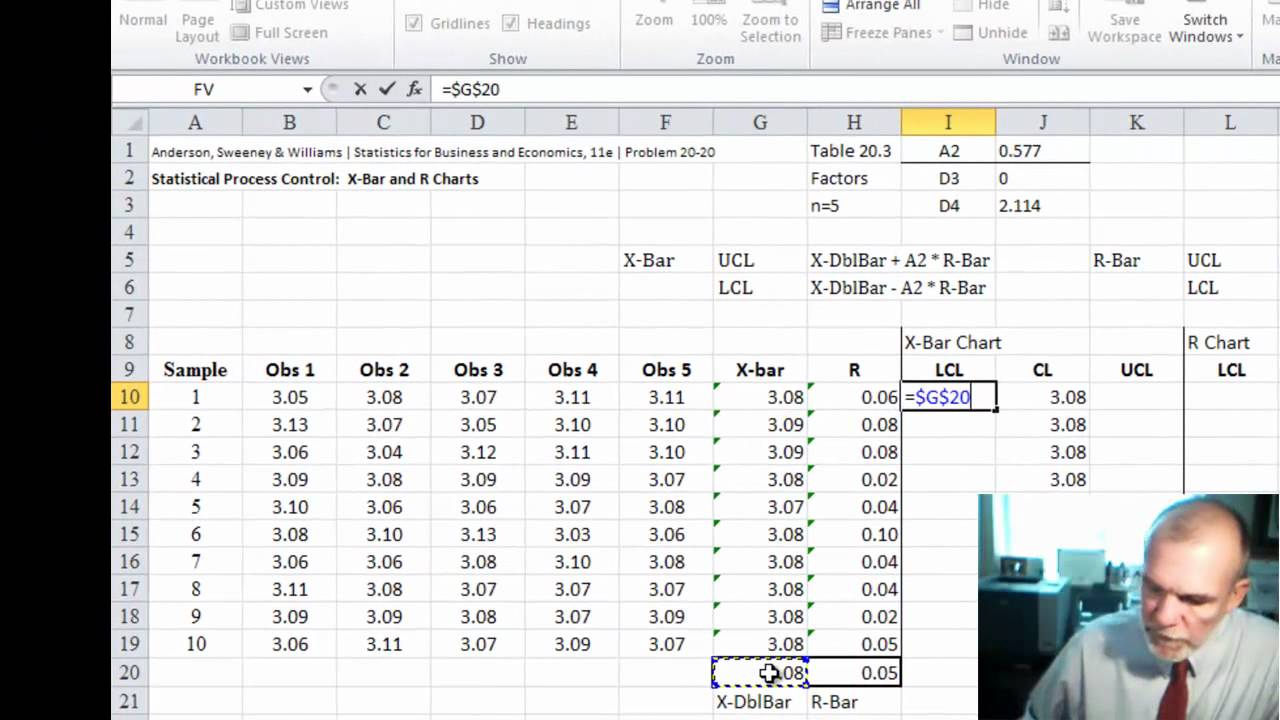

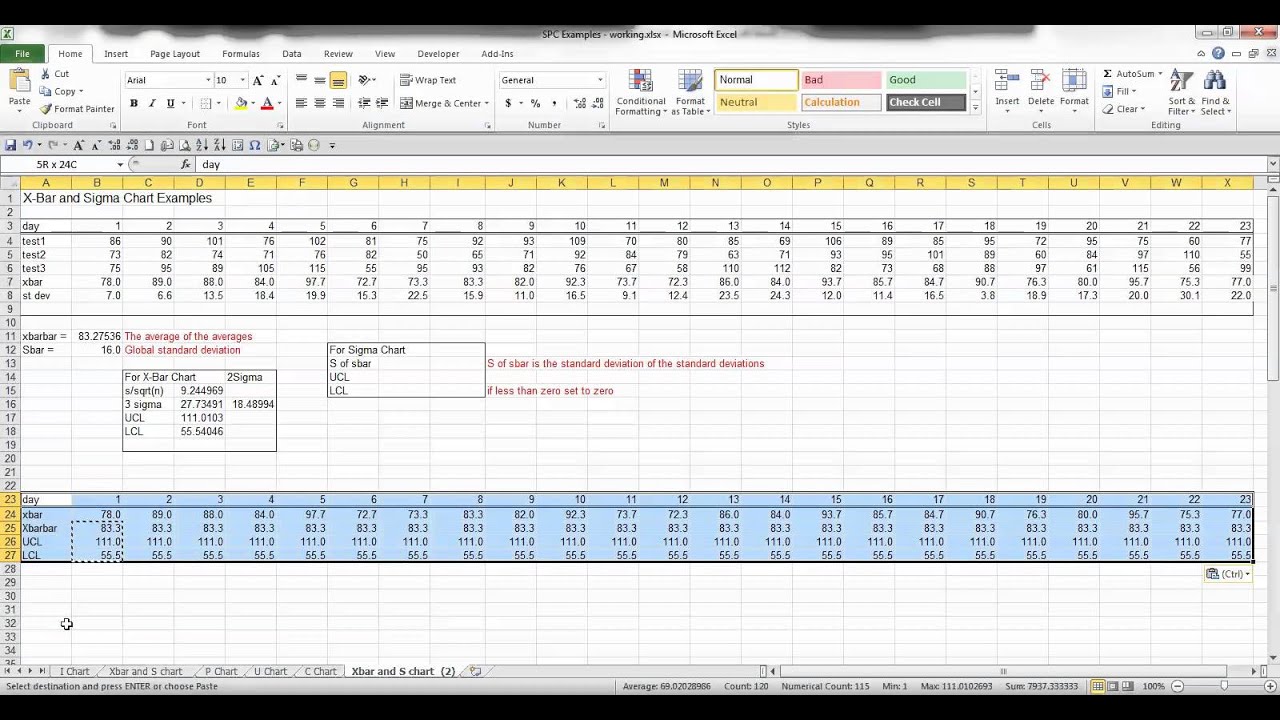

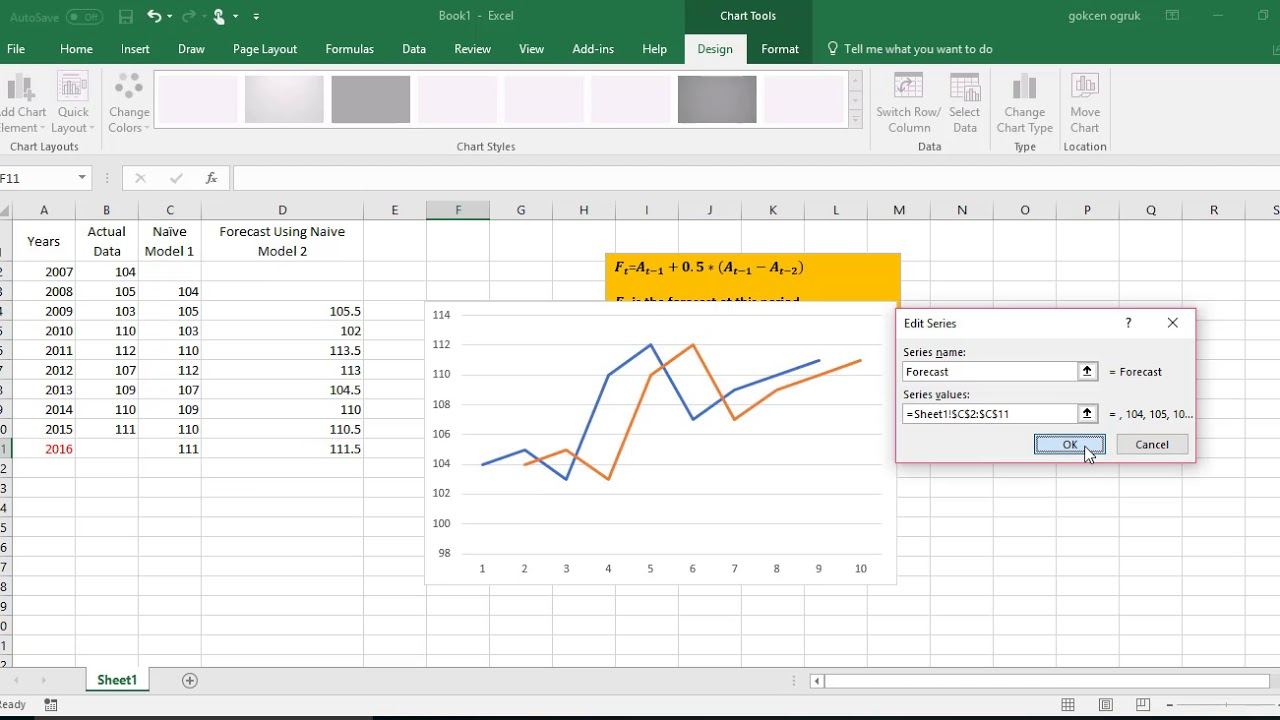

You may lose customers and sales due to unresolved quality issues.Minor issues snowball into much larger crises because they remain unresolved.Quality and performance suffer because there is an existing issue that you may need to resolve.Neglecting these insights leads to several problems: On the other hand, if your data deviates from the normal or expected performance limits, it’s an example of a control chart that requires action. You shouldn’t make changes in these cases because it may needlessly spend resources and potentially cause the process more harm than good. In other words, a process in control doesn’t need any adjustment. There may be some variation, but it’s within the natural range for this process and an acceptable level of deviation.Īfter all, no process runs at complete efficiency 100% of the time. When the analysis of your control chart reveals that your process is in control, it means that things are stable. More specifically, control charts let you know when your results are in control (in other words, performing at an expected level) or not.Įssentially, control charts allow you to monitor incoming data and test whether a specific process is in control or not. It is a tool for visualizing data from a manufacturing or business process.Īnother name for a control chart is a statistical process control chart (SPC chart for short) because it depicts data from a statistical process. Control Charts DefinitionĬontrol Charts are commonly referred to as Shewhart charts, Six Sigma charts, quality control charts and process-behavior charts. It wouldn’t take long for the Japanese manufacturing industry to champion the control chart to improve their processes.

Edwards Deming, a mathematical advisor of the United States Census Bureau and later the statistical consultant of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers after the conclusion of World War II.ĭeming was instrumental in spreading Shewhart’s thinking and the utilization of the control chart, particularly in Japan. His control chart presented the data in a way that helped businesses and manufacturers detect acceptable versus unacceptable variations in quality and performance. The problem was identifying when variation exceeded this acceptable range. The core principle behind Shewhart’s work was that any process has natural variation that is expected and acceptable. Essentially, Shewhart was laying the foundation and essential principles for what we now know as quality control management. To showcase his approach to quality control, Shewhart created a simple visualization, which later became the control chart. He utilized mathematical theories (normal distribution curve, standard deviation and others) to “normalize” manufacturing data and results. Shewhart’s approach was to categorize problems or performance deviations into two categories: common and special cases. It was costly to repair when these systems failed because much of the equipment was underground. While working for Bell Labs in the 1920s, Shewhart’s task was to improve telephone system efficiency.

It was a significant turning point where factory labor overtook the agricultural workforce.ĭuring this period, quality control engineers began to explore new tactics for refining the manufacturing process. The societal and political changes in the 1920s, punctuated by the title of “The Roaring Twenties,” tend to overshadow the tremendous industrial progress of this time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)